The Origins of a Lifelong Challenge

Born in 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama, Helen Keller’s life began like any other. However, at just 19 months old, a viral illness dramatically altered her life, leaving her deaf and blind. Medical experts of that era labeled it as “brain fever.” Today, many believe she suffered from scarlet fever or meningitis. Regardless of the exact cause, this profound disability thrust Keller into a world of silence and darkness, isolating her from the vibrant life around her.

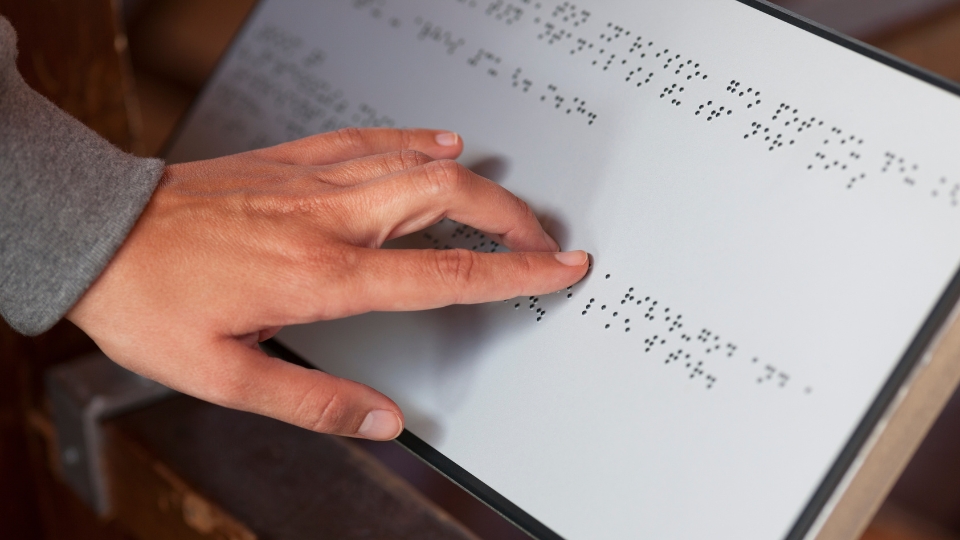

Initially, Keller’s formative years were fraught with frustration. She struggled to communicate and connect with her family, which left her feeling trapped in her own body. However, her story took a pivotal turn when she met Anne Sullivan, a determined teacher who would become her beacon of hope. Sullivan’s tireless commitment to Keller’s education enabled her to learn various forms of communication, including sign language and Braille. This transformation not only opened the doors to education for Keller but also propelled her to become an influential figure advocating for people with disabilities. The 1962 movie, The Miracle Worker, does a great job telling the story of Helen Keller and her teacher, Annie Sullivan.

Breaking Barriers through Education

Keller’s relentless pursuit of knowledge culminated in remarkable achievements. After years of dedication and hard work, she became the first deaf-blind individual to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree from Radcliffe College. This milestone shattered societal perceptions about education and disability, proving that determination, when met with the right guidance and resources, can lead to extraordinary outcomes.

Keller’s passion for learning didn’t stop at her formal education. She continued to write, penning several autobiographical works, with The Story of My Life being a standout. This book resonated with readers worldwide upon its release, revealing her struggles and triumphs in a way that inspired countless others. Keller’s eloquence and insight showcased that even those facing immense challenges could contribute significantly to society, challenging the very notion of being a “flawed design.”

A Voice for the Voiceless

In addition to her academic success, Keller became a tireless advocate for social justice, championing the rights of people with disabilities. She traveled extensively, delivering lectures that illuminated the needs and capabilities of the disabled community. Her advocacy extended beyond just disability rights; she spoke out against discrimination, poverty, and war, rallying support for various humanitarian causes. Through her powerful voice and unwavering spirit, Keller became a symbol of triumph over adversity, inspiring millions to advocate for change.

Keller’s legacy endures in the organizations she helped establish, including the American Foundation for the Blind, which continues to support and empower people with visual impairments. Her life embodies the idea that what society may initially perceive as “flawed designs” can ultimately lead to profound impact and understanding. Keller’s remarkable journey serves as a reminder that resilience can defy expectations and transform the world around us.

Keller was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964 in recognition of her remarkable accomplishments and activism. She passed away in 1968 at the age of 87, leaving behind an incredible legacy as a trailblazer and inspiration.

Conclusion: There are no flawed designs

As you recall, in the initial post, we concluded that a good design meets three key criteria; a good design:

- resonates with other people;

- offers tangible benefits to mankind, in general, and to each of us that interact with the design directly or vicariously; and

- leaves a lasting impression.

And while, at first blush, Nick Vujicic, Stephen Hawking, and Helen Keller may appear to be “flawed designs,” I trust now that you see each one of these amazing people meet the requirements for good design.

And if each of them are good designs, that means the same is true of all of us.

You Are Not A Cosmic Accident!

Curious to learn more about Helen? You can get her autobiography here.

Would you like to determine your unique design? Click here to learn more about a tool that’s been developed and refined for over 100 years that measures your aptitudes and then shows you the careers that fit your unique design.